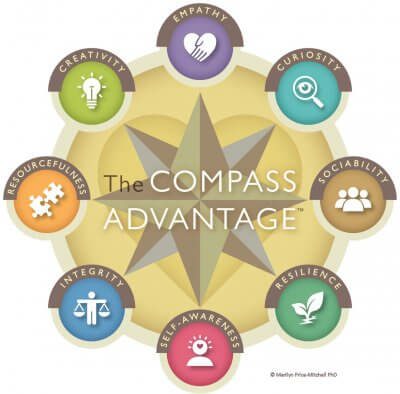

Theories in human development have driven our research at Roots of Action for more than a decade. The Compass Advantage framework is a simple and engaging lens to understand core abilities that contribute to human thriving. Through this lens, individuals, parents, schools, and communities can learn to strengthen abilities that have been shown to nurture human development from childhood through older age.

Our research began with a focus on adolescent development. We wanted to know how adults nurtured the development of young people in ways that fostered their engagement as responsible, participatory, and justice-oriented citizens. We soon learned the abilities that propelled youth to become purposeful citizens were the same ones that fostered human development at all ages. While Roots of Action shares articles and resources that bolster positive youth development (PYD) from kindergarten through high school, it is important to understand that the long-term goal of PYD is to promote healthy development throughout a lifetime.

What is Human Development? Why is it Important?

Human development centers on strengthening the attributes and abilities that help people flourish in life. According to the United Nations, it “is about giving people more freedom to live lives they value. This means developing people’s abilities and giving them a chance to use them.”

For young people, human development involves nurturing abilities that help them decide what matters most in life and encouraging them to determine and navigate their own paths. It is about facilitating meaning and purpose, rather than using grades and test scores as the sole measurement of self-worth. For adults, human development involves fostering abilities that give people the opportunity to live lives they value rather than using income as the sole measurement of success or wellbeing.

Human development is an important area of study. Multidisciplinary research shows that people can improve their lives and wellbeing at any age by enhancing their human abilities through positive relationships, experiences, and opportunities. In addition, the Human Development Index (HDI) is a tool for assessing a country’s development by the health and wellbeing of its citizens, not by economic growth alone.

Erik Erikson (1950) developed a theory that outlined eight stages of human development, from infancy through old age. Yet regardless of age or stage, there are core underlying abilities that are linked to human thriving throughout the lifespan. Development that begins during childhood is interconnected with adolescence and adulthood. That is why our current research using the self-administered Compass Survey of Core Human Attributes spans the ages from five through adulthood.

This article provides background on the research in human development that was used to create the Compass Advantage framework and the compass surveys. It is most helpful for those interested in using our work within schools, nonprofits, and organizations; and for researchers who wish to understand the concepts behind our work.

A Framework for Understanding Human Development

The compass framework supports the concept of human development as envisioned by the United Nations. It also supports diverse educational frameworks, including Social Emotional Learning (SEL), developed by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (Dusenbury et al., 2015); the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the Framework for 21st Century Learning, developed by Battelle for Kids.

Beyond educational equity, the compass framework focuses on achieving developmental equity—the right of all children to have the relationships, experiences, and opportunities that help them thrive in school and life.

One of the premises of research in the field of positive youth development is that strengthening personal abilities, attributes, competencies, and civic values in young people promotes human development throughout the lifespan (Benson et al., 2007).

Researchers in youth and adult development have identified a variety of human attributes that enable individuals to positively contribute to self and society. Since Peterson & Seligman (2004) classified twenty-six character traits and six virtues associated with human development and thriving, thousands of studies have shown how internal abilities contribute to agency and wellbeing (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

The Compass Advantage framework is grounded in systems theory. Our research explored the patterns within broad categories of abilities practiced regularly by exemplar youth. We discovered that young people who became agents of social change regularly demonstrated and practiced eight core abilities—curiosity, sociability, resilience, self-awareness, integrity, resourcefulness, creativity, and empathy—by the time they reached the end of high school (Price-Mitchell, 2010b, 2015). These teachable abilities are key components of social and emotional learning (SEL) and used to foster developmental and academic competencies in preschool through high school-aged students (Dusenbury et al., 2015).

These eight abilities have been widely studied as individual constructs by other researchers and found to be important for youth, adult, and societal thriving. Our research suggests there is a systemic connection between the eight abilities, meaning they work together toward the attainment of wellbeing.

Below is an overview of each ability as defined and measured by the Compass Survey of Core Human Attributes.

Empathy is the ability to recognize and respond to the needs and suffering of others.

Curiosity is the ability to seek and acquire new knowledge, skills, and ways of understanding the world. It is at the heart of what motivates kids to learn, provides a key pathway to student success, and keeps young people learning throughout their lives. Curiosity facilitates engagement, critical thinking, and reasoning.

Sociability is the joyful, cooperative ability to engage with others. It is derived from a collection of social-emotional skills that help students understand and express feelings and behaviors in ways that facilitate positive relationships, including active listening, self-regulation, and effective communication.

Resilience is the ability to meet and overcome challenges in ways that maintain or promote wellbeing.

Self-awareness is the ability to examine and understand who we are relative to the world around us. It is developed through skills like self-reflection, meaning making, and the process of honing core values and beliefs.

Integrity is the ability to act in ways consistent with the values, beliefs, and moral principles we claim to hold. Rooted in centuries of moral philosophy and ethics, integrity is derived from the Latin word integritas, meaning wholeness.

Resourcefulness is the ability to find and use available resources to achieve goals, problem-solve, and shape the future. The literature on resourcefulness focuses on a common theme—the processes by which humans achieve goals.

Creativity is the everyday human capacity to produce new ideas, discoveries, and processes.

Human Development in Standards-Based Education

The Compass Advantage framework and the Compass Survey for Youth Ages 10-17 can be easily integrated into a standards-based curriculum to bolster the knowledge, skills, and abilities that students are expected to possess at critical points in their education.

The framework supports Social/Emotional Learning Standards, including those developed by the Illinois State Board of Education. Their three SEL goals include:

- Develop self-awareness and self-management skills to achieve school and life success.

- Use social-awareness and interpersonal skills to establish and maintain positive relationships.

- Demonstrate decision-making skills and responsible behaviors in personal, school, and community contexts.

With its focus on positive youth development and social-emotional learning, the compass framework also supports the mission of many kinds of schools, including the International Baccalaureate (IB) Learner Profile.

Learn how to use the compass surveys in the classroom and how to spark conversations about inner strengths.

Role of Psychological Wellbeing in Human Development

Psychological wellbeing generally refers to a “combination of feeling good as well as actually having meaning, good relationships and accomplishment” (Seligman, 2011, p. 25). Researchers examining human thriving across the lifespan often conceptualize the term as a growth-oriented, developmental process (See, e.g., Benson & C. Scales, 2009; Bundick et al., 2010; Lerner et al., 2003). Su et al. (2014) defines seven core dimensions of psychological wellbeing, the first being subjective wellbeing in the form of high life satisfaction and positive feelings. Subjective wellbeing is known to be an internal barometer of how other aspects of psychological wellbeing are currently satisfied.

A core aspect of our research at Roots of Action involves studying the association between subjective wellbeing and the practice of curiosity, sociability, resilience, self-awareness, integrity, resourcefulness, creativity, and empathy in youth and adulthood.

Our research in human development and how it is linked to thriving is ongoing. Preliminary data suggests that when young people and adults practice all of the eight compass abilities in their daily lives, they report higher levels of subjective wellbeing.

References

Benson, P. L., Scales, P. C., Hamilton, S. F., & Sesman, A. J. (2007). Positive Youth Development: Theory, Research, and Applications. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0116

Bundick, M. J., Yeager, D. S., King, P. E., & Damon, W. (2010). Thriving across the life span. In R. M. Lerner, M. E. Lamb, & A. M. Freund (Eds.), The Handbook of Life-Span Development. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470880166.hlsd001024

Dusenbury, L. A., Newman, J. Z., Weissberg, R. P., Goren, P., Domitrovich, C. E., & Mart, A. K. (2015). The case for preschool through high school state learning standards for SEL. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich, R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook of social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp. 532-548). Guilford.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. Norton.

Lerner, R. M., Dowling, E. M., & Anderson, P. M. (2003). Positive Youth Development: Thriving as the Basis of Personhood and Civil Society. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 172-180. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_8

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

Price-Mitchell, M. (2010b). Civic learning at the edge: Transformative stories of highly engaged youth [Dissertation, Fielding Graduate University]. Santa Barbara, CA.

Price-Mitchell, M. (2015). Tomorrow’s Change Makers: Reclaiming the Power of Citizenship for a New Generation. Eagle Harbor Publishing.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Su, R., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 6(3), 251-279. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12027

How to Cite this Article (APA)

Price-Mitchell, M. (2021). Human Development is Fundamental to Thriving. Roots of Action, https://www.rootsofaction.com/human-development/